DO WHAT YOU CAME HERE TO DO (FOR HOLY WEEK)

The King comes riding into Jerusalem, on the back of a borrowed donkey. The man rides like an apology, a slapstick parody of power, a send-up of pomp and circumstance. The man rides under the weight of all our collective loneliness, as well as his own. With no stallion, no army, and no pretension, Love himself rides solo in the parade of powerlessness. Royalty, at last, has no entourage.

With apologies to Dante, this is the original divine comedy, a moment more Mel Brooks than Michelangelo. Yet the man of sorrows is not a shtick. He is the embodiment of all our dreams, and the incarnation of all our wounds. He is love personified. He is not quite the lone rider of some apocalyptic Johnny Cash song—He is the song of songs, he is music itself. He is the only one to ever actually bear the weight of the world on his sagging shoulders. There is a fire in him, a flame of love. But there is also a terrible tenderness—eyes as big and black and open as the face of the sorry beast that carried him.

Christians call this scene “the triumphant entry,” but the man makes triumph into a joke, because the parade is the beginning of a death march. If this is triumph, this scene radicalizes the term—evidently, triumph must look an awful lot like being triumphed over. As his body jiggles on the donkey, fumbling through the stone streets of the holy city, the people wave palm branches, and shout “Hosanna in the highest!” Palm branches flail in rapid motion, a mid-eastern forest of Hallelujahs. And yet underneath it all, runs an ancient sadness.

God is on his way to die, as vulnerable to the elements as any other man or woman has been. His chest, like his heart, is open—the hen with her breasts exposed, her wings extended, longing to gather her chicks under her wing. But soon, her sacred breast will be wounded; her open chest taken as an invitation for her ripping.

But love does not protect itself from spears or spit or swords. His ribs, like his eyes, are exposed. Rods and whips and nature itself will have their way with him, nails driving into dirt olive skin like an animal. His body will be bent and twisted like a rag doll, like a puppet.

Still he rides into Jerusalem, vulnerable. He keeps on coming the way love always comes—defenseless.

A few days later, the man of sorrows walks the solid ground of the garden, but he is all liquid now. His bowels are water, his sweat is blood, his heart melted wax. He has prayed to escape his fate, but he hears fate coming for him in the low rumble of Roman boots on the ground. All he wants is the same thing anyone of us wants when the pain is too deep for words—someone to share it with. But as he turns his head towards the gathering storm, he sees his friends crumpled in the grass, sleeping.

He sees a familiar face in the middle of the platoon, the only face he can find as haunted as his own. The man’s eyes are empty, but his lips are full as they graze his face—kissing him. His kiss, perhaps like most kisses ultimately, is a betrayal. Still he speaks softly to Judas, a word full of laughter and play and shared experiences, “Friend.” He says it without a trace of sarcasm. “Friend. Do what you came here to do.”

He does not reach for control, or surge at him in retaliation. Love would rather be seized, than to seize. But Peter, his hot-blooded disciple, will have none of it. He has not yet learned Master’s way of terrible tenderness. He, like so many of us, is a practical man, needing to grasp for control of the chaos around him. Instinctively, he wraps his tense fingers around his sword, unsheathes it—and swings, wildly in the direction of a man named Malchus, the servant of the high priest, hacking off his ear in a single stroke. The man screams in terror, the little red-soaked lump of cartilage lying on the ground.

The man of sorrows, all water now, speaks yet with the strength of many rivers: “Put away your sword. For those who live by the sword, die by the sword. Do you think that I cannot appeal to my Father, and he will at once send me more than twelve legions of angels?” Love stoops then—like it always does—and picks up the gory lump. Malchus hears nothing as the man approaches him, conscious only of the searing pain, his hands pressed hard against the hole in the side of his head. Gently, Jesus moves his hands, presses the ear firm to the gaping wound—and he stops screaming.

A disciple of Jesus cut rather than healed, and Jesus had to come behind him to clean up the mess made by one of his own. He’s been doing it ever since.

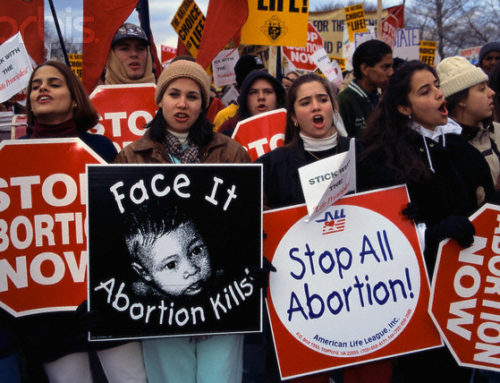

Jesus’ humble ride into Jerusalem shows us the way of the kingdom, for it is the way of the King who inaugurated it. Peter’s rabid act of fear, fear of his God being taken from him and naked fear for his own life, shows us the way of the kingdoms of this world. One is the way of vulnerability, humility and sacrifice, one is the way of violence, retaliation and retribution. One is the way of being seized, one is the way of doing the seizing. One says “friend, do what you came here to do.” One takes matters into it’s own hands. One is the way of the kingdom, one is the way of the empire.

Peter, well-intentioned, wants to protect Jesus and protect himself. But the One who has been raised from the dead, and long before had legions of angels at his disposal, is in no need of our protection. He is in no need of our passionate displays of piety. Jesus is not looking for anyone to stand up for him.

And yet, throughout the life and ministry of Jesus, we see him standing with others. We see him standing between the accused and the accuser, when the men came for the woman who had been caught in adultery. He stands with despised tax collectors and for the woman at the well. While the Son of God is in no danger, people on the margins of our societies are in great danger indeed—and Jesus asks us not to stand up for him, but to stand with him. Jesus asks us to stand alongside him, by standing with them.

Still today, the choice is ever before us, to go the way of the king or the way of the kingdoms of this world. It is often obscured, because the way of the world often comes packaged to us in the language of piety, devotion, self-righteousness, common sense, and self-protection. It often comes cloaked in the language of blame and scapegoating of someone who is other—and it is a kind of righteousness indeed, the righteousness of cleansing one’s self at someone else’s expense. The energy of such violence is primal, tribal, and does in fact have a kind of raw, explicitly religious power.

But it is an energy rooted in fear. Peter’s posture of defense, is a posture that love (self-giving in nature) never takes. It is this kind of fear that perfect loves comes to exorcise. And make no mistake—fear is a demon that love, and only love, can cast out.

Source: http://www.jonathanmartinwords.com/blog/2017/4/13/do-what-you-came-here-to-do-for-holy-week